They were the scions of humankind’s greatest dreamers, destined to die on the Ark.

Forty-six years after being wrenched from the warm embrace of Earth’s orbit, three generations of pilgrims hurtled through deep space, like a single snowflake carried by capricious arctic winds on a moonless night. Multiple generations planned to live and die in transit so that their grandchildren could have grandchildren who would live on their new home. Their religion was life, and their promised land was Proxima Centauri-XR-4, informally called Genesis.

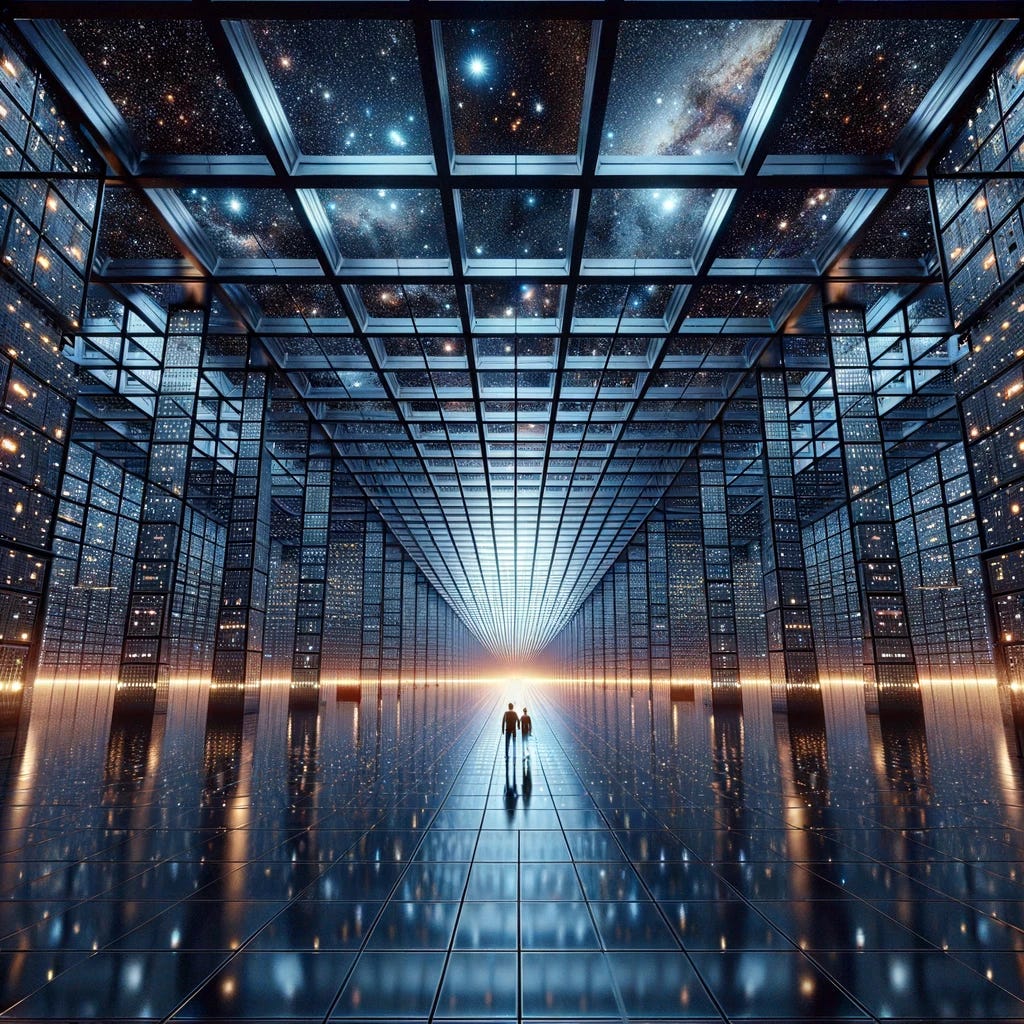

When the Ark was being built, a contingent of engineers argued that the observation deck was implausible, a waste of space and resources. But the planners said it was non-negotiable. It was four square miles of steel. The ceiling was made of enormous windows, each the size of a city block, set in a massive grid-patterned bezel. At the intersection of each bezel, a square pillar came down to the floor. The width of each pillar was the same as four adult men spreading their arms and touching hands, and the height was such that it could fit four bedrooms stacked on top of one another.

The planners raged in debates for years about the allocation of resources and the engineering it would take to build the observation deck. But in the end, they all understood that seeing the stars is how the pilgrims would see their purpose. Someone born on the Ark would not have the Spartan fanaticism of the planners, and they would need a place to be inspired in their mission. Not being able to see the stars would mean they could never see themselves: martyrs for Genesis, saviors of humankind. So just as it was important to have engineers who cared for the ship, doctors who cared for the pilgrims, horticulturists who cared for the food, and scholars who cared for the mission, the ship would also need technicians who cared for the windows.

Seventy years after the planners’ last debate concluded, Bill slowly drove his cart through the observation deck. The cart was like a miniature truck with no roof or doors. It could drive itself but Bill was old-fashioned. He liked to steer it himself and whistle along to old songs from the ship’s archive. He would often work overnights and pick up shifts nobody else wanted because he enjoyed the work and having the deck to himself. So he was surprised when he passed the last pillar and there was already a cart where he had planned to park his own.

“I thought I was the only one working today.” Bill said. Anna was leaning against her own cart, looking down engrossed in her screen. She looked unusually disheveled.

She yawned then smirked, “Is that why you didn’t mark the ticket filled?”

Some of his younger coworkers would do impressions of Bill, popping out from behind a pillar to shout, “Ticket!?” Despite being affable and laid back, Bill was a notorious stickler about the ticket system that notified them when there were custodial or maintenance issues. Anna held up her screen, showing she had clearly marked the ticket filled.

“I was going to do it when I got here,” Bill said. He smiled and Anna understood why they still told stories about ‘Wild Bill’ and how handsome and charming Bill had been as a young man. This further aggravated her mood.

Bill asked, “Were you asleep?”

Anna opened the seat where she had just been sitting and pulled out her beam light. Even the way she moved left no room for silliness or interpretation. “No, I was already up.”

“Well, let’s take a look then.” Bill turned the lights of the observation deck off via his screen, then they both looked up and pointed their beam lights at the windows.

They made an odd pair standing next to one another. He moved like an old dancer, smoothly gliding from place to place, wiry with a bit of a gut, graying around his temples with deep wrinkles outside each eye from a lifetime of wry jokes. She was compact, short but muscular and springy, with close-cropped hair and piercing eyes. She was all shoulders and walked on the balls of her feet as if she could pounce at any moment.

With the lights off, Bill and Anna were smothered in stars. They were a distance from their ancestral home that would have been inconceivable to the human mind for most of human history. Yet they both felt the chest-tightening, wide-eyed wonder that humans had felt since the first one thought to look up at night and contemplate their place. They were totally alone. If one of them squinted in any direction they might barely make out the edge of the observation deck.

Bill let a loud exhale through his nose. “It’s funny. When I was your age, this place would be packed for a view like this.” Bill said. The night sky through the windows was pure stars.

“People still come up sometimes, to jog.” Anna offered.

“Oh yeah,” Bill laughed. “The skylight marathon.”

They both scanned their beams over the windows in silence, looking for the missing window-cleaning drone that had gone off-network.

“Young people just aren’t as interested in the view,” Anna said. She didn’t sound angry, but she bit each word off as if it cost her to say it.

“When I was your age, it was the date spot. That’s probably why there are so many women your age named Star.” Bill laughed, “We weren’t a very imaginative generation, I guess.” He paused. “I think during the daytime you still get a lot of people my age up here because they’re nostalgic. There are still a few old-timers like me who were born on Earth.”

Anna let an uncharacteristic sigh escape. She often grew bored of Bill talking about being born on Earth, but it was unlike her both to make a noise against her will and to let someone know how she felt.

“Got it,” Anna said. Her beam light wasn’t on the window directly above them. It was focused on a small black disc slowly moving across the window to their left, across the next bezel. Bill and she walked over until they were almost directly under it.

Bill laughed. “I’m impressed you could see that drone. Even with the beam, it would have taken me an hour or so to find it.”

Never one to acknowledge compliments, Anna held her screen up and pointed it at the drone on the ceiling window. After a few moments, her screen lit up, and a corresponding light on the drone turned on. She grunted to herself and brought the screen down in front of her and tapped it a bit. “Yes. That’s why it went off network.” She looked at Bill and pointed up, “This window was already cleaned last week.”

Bill had been watching Anna’s screen to watch her work. He had five times her tenure working on the windows, but she was much more efficient. He admired her fluency with the drone interface.

After a few taps on Anna’s screen, a personal message popped up. Bill read it out of habit <what’s up with you -GREG> before he noticed it was from Anna’s boyfriend and he turned away. Anna swiped the notice away, embarrassed. She looked back to her cart and swallowed, “OK, we found it and got it reconnected, I’m going to head back.” Her voice had quavered a bit.

Bill raised his eyebrows and pulled out his screen and pressed it a few times. “Why don’t you stick around with me?” Anna was so tightly wound and self-contained, that she often made Bill feel like a slacker. He was already going to her for help more often than the reverse. But her not being as buttoned up this evening combined with the message made Bill wonder if perhaps she was dealing with a more ordinary sort of problem, a life problem. And with those, his experience dwarfed hers.

Anna was turned and walking away from Bill when he gently called after her in a sing-song voice. “I already called for a ladder.”

Anna remained facing away from Bill, but the hardness left her body. Her shoulders dropped and she looked down at her feet. “What’s the point?” Bill made a surprised murmur and Anna continued, “It just goes back and forth. It cleans for no reason.” Anna’s voice got stronger and angrier as she spoke. “Nobody is up here to see the view. The drone could break or disappear and nobody would notice.” She turned around and finished and let out a big exhale, then she finished, less in an angry voice than pleading with Bill, “It wouldn’t matter. Just let it clean the window it’s on.”

Bill’s face and posture softened. Where she stood looking at the floor, Anna was bathed in starlight and framed by endless pillars in every direction. She looked completely alone. Bill cocked his head to one side. “Yeah.” He said.

They both stood in silence for a moment until Bill took a big breath and looked up and away toward a cluster of stars he had been admiring for years. Anna followed his gaze. “You know Anna, I don’t think I’ve ever told you this, but when I was about your age, I was very disappointed that this was my job.”

Anna’s face whipped toward Bill. Her expression and sudden upright posture betrayed her shock. “My parents were young adults when they got here.” Bill continued. “They signed up and trained. They were real deal true believers until the very end. When I had my daughters, my parents would read them stories written on Earth that were about Earth. But my folks would always change the setting to Genesis. There was never a doubt, never a question about what they were doing. My Dad gave me this and asked me to bury it on Genesis.” He pulled a cross on a chain out of his shirt.

Anna took a step closer to see the necklace. Bill finished, “For all that, do you know what their jobs were?”

“Most first-gen were Agribay, right?” Anna asked.

“No, not really. Those are just the stories you hear the most.” Bill said. “My parents told people they worked in technology, but both of them worked in sanitation. On Earth, they had been trained scientists, foremost technologists of anyone they knew. But on the Ark, they would wake up every day, send me and my brother to school, and then take the tram to the recycler to train the sanitation algorithm. This sounds technical, but in reality, it was putting on a mask, goggles, and gloves, and sorting trash. For over thirty years, they would go in and sort and categorize the waste that the machines didn’t recognize. Of course, it got easier over time, but at first it was a demeaning, never-ending parade of other people’s waste.”

Bill looked right at Anna and raised both eyebrows. “I never heard them complain.”

He looked back at the skylight at an angle far away. Anna followed his gaze again, expecting an explanation to come from there.

“After school was over, my brother went to advanced cultural studies. I did all the internships and apprenticeships in technology I could. I learned so much and had a great time. I fixed things before we had all the drones dialed in. I worked on media delivery before all the screens were linked. I even got to do some security. That was wild.”

Bill took a deep breath and looked back to Anna, “I didn’t want to commit, but when I was a little older than you, 26 I think, it got harder to get internships and apprenticeships. I wasn’t old enough yet to be a career change intern, and I was too old for the post-studies roles. So I went back to every place I’d worked and they were all filled. Dejected, I told my parents. They were the ones who introduced me to Dee, which is how I ended up here.”

“That’s . . . ” Anna said. She was rarely at a loss for words, so wasn’t practiced in trailing off trying to finish a sentence without knowing what to say.

“Shocking, I know,” Bill said. Bill started fiddling with his screen and Anna looked him up and down, seeing him as if for the first time. He suddenly looked so old. She thought back to his unbridled enthusiasm in her first week of training, how he’d whistle on the way to reset drones, and once a month would lead everyone in a manual clean, listening to music and asking people about their lives.

“After I had this job for a few months, I had money to spend and was feeling good about myself, but one day I ran into an old friend with my brother. I was so envious of them both: their position and their certainty. They had both started careers as a historian and a doctor. A darkness filled me and all I could talk about was how much I hated my job and how I deserved better. Then I started to openly question whether anything I did mattered at all.”

Bill leaned against his cart. “Finally, one night I was bringing a woman to meet my parents for dinner. We did not last long but she encouraged the ambition I used to mask my discontent. During the dinner, I said something to my father to the effect of, ‘since we will all die on this ship, I might as well make as much money and prestige as I can now.’ He did not react strongly, but a few days later I received a message from him that he wanted me to join him for a work day.”

“That was when I learned the real nature of his job. That day’s work was the hardest, grossest work I ever had to do. I think he had saved up the heaviest, nastiest stuff for weeks in anticipation of my visit. And each time we pulled something out he told me what it probably was, how he was going to categorize it, and why. I’m talking rotting food, feces, burnt metal, and other stuff of nightmares. It was the longest day of my life ”

While Bill was laughing, a third cart appeared from behind a pillar and then gently hummed as it rolled up to them. Bill grunted in its direction to bring Anna’s attention to it. Unlike the two carts they rode, this one looked like an upright coffin. Bill walked up to it and tapped it with his screen, then walked directly under the drone. The unmanned cart rolled away then a ladder began to raise from the top of it. As it did so, Bill made eye contact with Anna and nodded to the drone, “stop the drone,” and then, with a smile, “please.”

Anna raised her screen in the direction of the drone on the ceiling and tapped it a few times. The drone stopped moving and a light on its back started flashing. A few moments later, the third ladder cart had extended all the way up to it. Anna sighed heavily and Bill said, “I got it.” He climbed up the ladder and pried the drone off the ceiling window, put it under one arm, and made his way back down slowly.

“Come on,” Bill said, nodding to his left, “let’s go put this up.”

Anna's screen flashed and she looked at it again. Bill caught Greg’s name, and this time Anna took time to angrily tap out an answer back. “Trouble in paradise?” Bill asked

“What?” Anna said.

“Sorry,” Bill answered. “It’s something my Dad used to say all the time.” He got onto his cart and put the drone on its back. “Ride with me.”

Anna reluctantly got into his cart and they began to ride. The ladder cart followed behind Bill’s cart. “Sorry,” she said. “I’m a bit on edge.”

Bill gave a small grunt of noncommittal support. After a couple of minutes of riding, he asked, “want to talk about it?”

“It’s nothing,” Anna said. They paused and looked around. Rarely did they take the time to really notice the grandeur of the observation deck. The planners were right that passengers would take time occasionally to look out into space, to think of Earth, and to dream of Genesis. They just probably hadn’t planned on it being mostly the custodial staff.

Anna turned to Bill. “Did you always plan for kids?” Her tone was brisk, on the verge of interrogation.

Bill laughed. “Yeah, most of us did. Pretty much everyone except the Benatarians. They thought that not having kids was taking a moral stand. There were way fewer people who just elected not to have kids like there are now. I think the Planners siloing the Benatarians actually had a lot to do with that. With them being out of sight, not having kids is not so much a political stance anymore.”

Anna answered, “Yeah, Greg and I planned not to.”

Bill grunted in surprise. He and Anna had talked enough that they had covered the major strokes of one another’s lives. He realized now the interrogation was a mask for vulnerability and stumbled over how to ask his next question. Finally, he settled on, “Planned?” emphasizeing the “-ed.”

“We still plan not to,” Anna said, matter-of-factly. She took a long pause. Bill let the silence expand.

“Greg likes to joke more than I do,” Anna said.

“Mm-hm,” Bill said, his eyes narrowed, trying to figure out where this might end up.

“In an effort to promote closeness, I have started making more jokes to Greg. But it comes off as gallows humor. It is usually dark.” Anna said. She paused.

Anna's lips were pursed so tightly that the skin on her face was changing color. She was straining to be as matter-of-fact as possible, and Bill could sense her tension, as she muscled downward into the seat next to him, trying to ground her feelings from escaping.

“I apologize, my mind is elsewhere,” Anna said. “But you know, duty is important to me.”

“Right,” Bill responded.

Anna’s body froze and then let out a long breath as if she had found something she was looking for. Bill could sense the tension in her melt away a bit, then she said, “people share unspoken agreements. Greg and I had an unspoken agreement when we met to never have children. We both believe in living here, now. We met over mutual disdain for the education videos about the importance of our children making it to Genesis. We called them propaganda.”

Bill’s opinions were widely known among his coworkers, so he said nothing. He did not think she was looking for that kind of response from him, and so he tried to make no moves, express nothing, to let Anna finish her point.

“Some jokes I made were about not having children because this is all pointless.” Anna waved her hand in the air. “Greg responded in kind. And this is why my mind is elsewhere.” Her face contorted. “It’s illogical. I joked about it first and he just repeated it. But when he says it, it makes me mad. I know it doesn’t make sense.”

Bill let the air hang for a minute and as kindly as he could manage said, “Yeah?”

Anna looked suddenly much younger and less militant as she looked over to him. “Do you remember Perry?”

“Of course!” Bill rolled his eyes and laughed. Perry had retired a bit too late. Anna and his time on staff had only overlapped by months.

“I never told you this, but I saw you that one time,” Anna said.

Bill paused because he wasn’t sure what she meant, then suddenly it came back to him. Perry had been old and simply refused to retire. He could no longer do the work that was required, so they gave him the most menial of tasks. He was a bit goofy and very forgetful and could hardly hear anything. Bill and some of the other staff teased him a lot, sometimes good-naturedly, and sometimes they went a bit too far, but they always apologized. And they always looked out for him. Bill in particular could do a funny impression of Perry that he would still do sometimes for the other techs who remembered Perry.

One day, Perry had been manually cleaning the observation deck, and a group of teenagers had been impersonating him, walking behind him, and dropping trash that he would have to double back and pick up. Perry did not catch on, and even struggled to notice when they started lightly pelting him with the trash so that it would bounce off of him.

Bill remembered it vividly because coming upon the scene he flew into a rage and yelled at the teenagers to leave. He even scared Perry, who hadn’t realized the teenagers were making fun of him. Bill picked up the trash and gently dismissed Perry. But what he remembered most about the encounter was the hot shame he felt as he realized how angry he was at those boys for doing something similar to what he normally did to Perry.

After that, Bill had called a meeting of all the techs but Perry, obliquely described Perry’s encounter with the teens, and shared his shame that they hadn’t treated him right. He told the other techs how the teenagers had held a mirror to his behavior and he didn’t like it. After that, almost nobody picked on Perry. It had made an impression on Anna, not because she thought it was necessarily the right thing to do, but because Bill’s candor had been unexpected, and because she had thought the teasing was unprofessional in the first place.

Bill looked to Anna who nodded and said, “It’s like that. When Greg makes my joke, I cannot handle it.”

For a few minutes, the only noise was the wheels of the cart on the observation deck floor.

“It’s a heavy thing to joke about.” Bill finally said.

“Yeah.” Anna sat up, “Thanks.”

“This feels like the old days,” Bill said and chuckled softly. “Dee and I used to go on inspections together all the time. Sometimes we’d talk but sometimes it felt like we were trading monologues.” The carts stopped and Anna’s screen began to light up. She took it out and held it up and it pointed a laser up to the ceiling. As she moved the screen around the laser stayed in a fixed point.

Without talking, Anna took the drone from the back of Bill’s cart and walked up the ladder to attach it to the ceiling window. After a moment it began rolling along, upside down, cleaning the correct window. She came back down and got into Bill’s cart. The ladder cart rolled off in a different direction.

“I understand about the joke; I think I get it.” Bill said. He tightened his grip on the steering mechanism. “The brother I told you about, he was a Benatarian.” Bill gave Anna a moment to absorb the shock. Bill was the last person she expected to have some dark, family secret. “He was one of the first to lock themselves away. It drove my parents crazy, obviously. Although the people in charge were less strict then. He would still come home for big holidays and the like. And being openly Benatarian was still legal. He would just talk about what he believed to anyone who listened. We always had a great time, but inevitably the conversation came back to ‘the discourse’ and his beliefs.”

Bill turned to look at Anna. “And I get it. It’s oppressive. It’s a black hole. It’s an idea that, if you accept its premises, smothers and suffocates you. It’s not new, either. I mean the Buddha said ‘life is suffering,’ but you didn’t hear Buddhists saying, ‘and therefore having children is immoral.’ But my brother fell under the influence of some sad, charismatic people. It was around the time that I was really complaining to my parents about how much I was owed and how pointless everything was that he disappeared.”

Anna could hear Bill swallow before he continued. “And he died alone in The Village.”

Anna said, “Wow, I’m sorry, Bill.”

Bill smiled, “Oh, thank you. But that’s OK. That’s old news. It was a long time ago. I was just sharing that to tell you I understand. The bleakness can pull you in, but it is hard to see it reflected in us. Just keep your head up.” He smiled at Anna, who gave a small smile back.

The cart arrived back to Anna’s cart and she got on it. “Have a good night,” Bill said, before turning his cart back.

“Bill,” Anna called to him. Bill stopped his cart and turned toward her. “Your story about your Dad. You hated your job at the beginning and end. What changed your mind? Was it the sanitation work?”

Bill let out a big laugh. “No! Oh, the work was the worst. I woke up the next day more pissed than ever. But I had the day off and my Dad showed up early to my house. He told me that I’d been so helpful he was ahead, and so took the day off. We went to eat breakfast together and he was in a great mood, but I was being a real moody shithead. When we finished eating, I was looking through my screen and he reached across the table and touched both my hands. He said he really loved having me at work with him, and that he understood where I was coming from. Then he said something I’ve thought about every day since then. He said that most of us aren’t born with an understanding of what our life means, and few of us are ever told what our life will mean. But we can decide that each little decision we make and each little action we take means something. And eventually, when we start to let the small things mean something, they accumulate and develop a gravity that is bigger than us. Without meaning there is a darkness that can consume you, and to make each choice mean something in its own little way, you eventually wake up one day and there are people who depend on you, and people you depend on, and things you care about. And on that day, the big, theoretical questions about meaning and what matters seem silly and hopelessly abstract. And you start to forget what the darkness looked like.”

Bill looked up at the stars and let out a soft laugh. Anna smiled back. “Anyway, see you tomorrow.” He smiled at Anna and his eyes creased. “We have some very important work to do.”

My name is Charlie Becker and I’m a writer, teacher, and bookseller. At least once a week—usually around Friday, I send out Castles in the Sky, a newsletter where I write the weirdest that feels right. If someone emailed this to you or you found it on social media, go here to learn more.

I went back and forth on this one for a while, special thanks to everyone who read an earlier version: Mak Rahman,

, , , , , , my Dad, and my wife.

Love this, Charlie—can't wait to read more.

Lovely story. Humans really don’t change, do they?