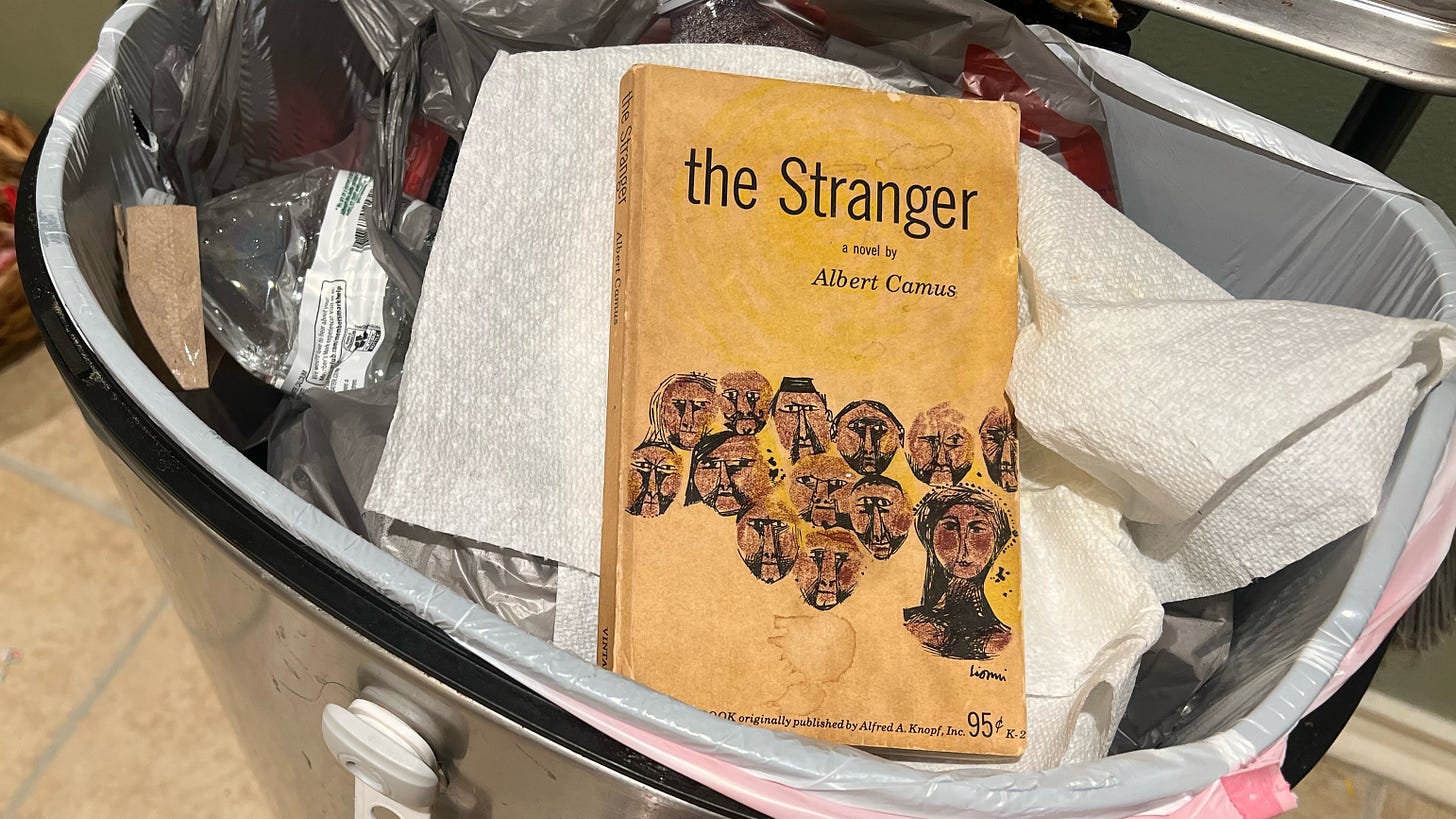

Reading The Stranger by Albert Camus made me realize why some philosophy has helped me to be clearer, happier, and more effective than ever, but some philosophy is a useless brain rot.

Becoming a father has made me both more action-oriented and more contemplative at the same time. Trying to educate myself so I can make the best decisions is what led me back to philosophy after abandoning it in my late twenties because I wanted to do more and think about stuff less. In reading philosophy, I have discovered two important distinctions. The first is between “just in time learning,” where I learn what I need to know to do the next thing, and “just in case learning,” where I learn something on the off chance that I need to know it someday. The second is between “books I want to read” and “books I want to have read.”

The Stranger is one of those books I always wanted “to have read” but never wanted to really read. The Stranger is the kind of book that I would have seen a woman reading in a cafe in my twenties and instantly decided she was too cool for me. Without ever researching it, I knew that it was associated with French intellectual life from the 20th century. It had a vague association with the word meaninglessness.

But I had no desire to read it. I’ve never cared to entertain or celebrate the idea that we’re all self-aware bacteria, or monkeys on a rock hurtling through the cold vacuum of existence into oblivion. As much as I wanted to be intellectually serious and see what the game was all about, it seemed a little dark but also mostly silly. I didn’t think I could hear or read anything that would convince me that existence is inherently meaningless, so the book never felt compelling.

Nonetheless, my intellectual vanity persisted, and I’ve owned a copy for years. Recently, I had a few hours to kill and grabbed the shortest book on my bookshelf which happened to be The Stranger. Reading it was an odd experience. The novel is not, in the conventional sense, good.

If you’re unfamiliar (spoiler alert), the plot of the novel is that the main character, Meursault, murders a guy on vacation and is arrested and sentenced to death. Are you curious as to why he kills the guy? So are most people in the novel, and those who have finished reading the novel. You know who is not curious? Meursault, the murderer. Not that he knows why he killed the guy–he doesn’t–he just isn’t curious.

And this is why Meursault and the novel irritate me. Meursault narrates and shares his thoughts, but he has almost no inner life. He has very few thoughts or preferences. He has almost no agency. Nothing affects him. He is more or less a “blank slate.” He just materializes one day, an aloof Frenchman in Algiers, with almost no strong feelings save a mild aversion to discomfort, no theory of mind for anyone else, and no real aspiration of any kind.

This is, for example, his inner monologue during his trial for murder:

It was quite an effort at times for me to refrain from cutting them all short, and saying: “But, damn it all, who’s on trial in this court, I’d like to know? It’s a serious matter for a man, being accused of murder. And I’ve something really important to tell you.”

However, on second thoughts, I found I had nothing to say. In any case, I must admit that hearing oneself talked about loses its interest very soon. The Prosecutor’s speech, especially, began to bore me before he was halfway through it. The only things that really caught my attention were occasional phrases, his gestures, and some elaborate tirades—but these were isolated patches.

Meursault is basically pathologically uninterested in anything happening. Even when he is being psychoanalyzed during his trial for murder, he cannot pay attention.

This persists all the way til the end of the book, when he has a small outburst that gives a little bit of color and seems to be what Camus was building toward. He is visited by a chaplain who basically tries to get him to find some solace in God–Meursault is an atheist–or carve some meaning out of his final days, but then when the chaplain persists, Meursault has an angry outburst. Meursault expresses his disgust with the chaplain and then shares a bit of his personal philosophy:

Actually, I was sure of myself, sure about everything, far surer than he; sure of my present life and of the death that was coming. That, no doubt, was all I had; but at least that certainty was something I could get my teeth into—just as it had got its teeth into me. I’d been right, I was still right, I was always right. I’d passed my life in a certain way, and I might have passed it in a different way, if I’d felt like it. I’d acted thus, and I hadn’t acted otherwise; I hadn’t done x, whereas I had done y or z. And what did that mean? That, all the time, I’d been waiting for this present moment, for that dawn, tomorrow’s or another day’s, which was to justify me.

And in my naive opinion, this seems to be the point Camus is making with the book: the only guarantee is death, what you do before then doesn’t matter. Life is absurd, unjust, and meaningless.

To be honest, if I had just found this book on the floor of my bookstore and read it, I would have abandoned it before the end. And if I’d finished it, I would have just thought it was a bad book. But because it was so famous (with over one million reviews on Goodreads, and Le Monde named it the best French novel ever), I decided to see what I’d missed.

After some googling, I discovered that Camus championed a philosophy called Absurdism. This philosophy acknowledges the Nihilist perspective that life lacks inherent meaning but suggests confronting and embracing this void. Instead of resorting to despair or concocting a constructed personal philosophy to fill the void, Camus advocated for living authentically and finding contentment despite the inherent absurdity of existence.

I agree with Camus’s suggestion in a sort of roundabout fashion, but I still feel how I felt before I read the book. I don’t care to entertain or celebrate the idea that we’re all self-aware amoebas, growing like a fungus near heat vents that can write music and send itself emails. Now that I’ve taken a step toward intellectual seriousness to see what the game is all about, it hasn’t convinced me that existence is inherently meaningless. Even though I understand now that it’s a cautionary tale, I didn’t find the book particularly compelling and am not sure I’d suggest it to someone.

The Stranger, however, was clarifying in that it helped me understand the problem I have with current philosophy and nihilism generally.

Nihilism is the belief that life lacks intrinsic meaning, value, or purpose. You may have heard of existentialism, which is a response to nihilism, and contends that human beings have agency and, despite life lacking intrinsic meaning, value, or purpose, they have the power and responsibility to create these things for themselves. Absurdism, Camus’ philosophy, is another response to nihilism. It posits a fundamental conflict between humans' inherent desire for meaning and the indifferent, chaotic universe, and it encourages people to live authentically and defiantly in spite of the Absurd. Existentialism and Absurdism are both suggestions on how to live in the face of Nihilism.

Reading The Stranger made me realize that Nihilism is the functional opposite of the philosophy I have been most attracted to lately, Pragmatism. Pragmatism is an American philosophy that posits that the value of a belief is what happens if you believe it. Becoming a father, growing in my career, trying to run a business, deciding how to vote, how to spend my time, how to spend my money–all of these issues have benefited from my recent reading of philosophy, specifically Pragmatism. To consider both Nihilism and Pragmatism are one thing called Philosophy is a pretty stunning oversimplification. Nihilism is the rejection of meaning, whereas Pragmatism is a practical approach to solving the problems of life with philosophical tools.

When I was younger, I did not want to confront Nihilism out of fear, but I sat and entertained it for years. I asked myself how my life would be different if it were true. I wondered how my feelings would change if I could convince myself life lacked value, meaning, and purpose. The conclusion I came to is that Nihilism requires a sort of religious faith. There is a concreteness and certainty to the conclusion that life lacks value, purpose, and meaning which you really only find in religion. If you are going to invent abstract thought experiments irrelevant to our lived experience, of course the logical conclusion is that life inherently lacks value, purpose, and meaning. This is the natural end result of abstracting away from everything that we intuitively know about existence.

Have you ever had a friend who was insecure and was convinced they were ugly or unlikeable? Have you ever had a friend who was so insecure that you literally could not convince them otherwise? In a weird way, this unshakeable certainty requires a sort of hubris. Your friend is saying that, “yes, I am unlovable, but my ability to determine what is lovable and what is not is actually so strong that nothing can shake me of my opinion.”

If you’re stuck with nihilism, then absurdism and existentialism are the best responses I guess, but I disagree so profoundly with the premise of nihilism in the first place. In a strange way, nihilism is not an organic stance born of observation and deduction, but rather a direct response to religion. It’s like your friend knows they’re not the best-looking person, but they couldn’t just be an average-looking person, they have to be profoundly ugly. There is a narcissism that runs through this. Similarly, if life is not derived from the divine mandate of a deity, then obviously it must be completely devoid of meaning. There is a similar narcissism to this.

And this is what bugs me about Nihilism and The Stranger. In The Stranger, Meursault is a blank slate etch-a-sketch person with no agency, preferences, or worldview to discern. He is devoid of all the things that make a person a person. Similarly, nihilism is devoid of all the things that make life life. Both are only possible if you strip them down to the barest abstraction.

I'm Charlie Becker, a writer, teacher, and bookseller obsessed with big ideas. Every Friday, I publish Castles in the Sky, a newsletter about combatting intellectual loneliness and existential boredom.

Rabbit Holes

Every week I’ll share a few links or ideas to things I think are interested and (at least a little) related to this issue of the newsletter.

Synecdoche, New York

As provocative and silly as the title of this essay was, and as much as I bag on Absurdism here, I think exploring the meaning of life (or lack of it), makes for profoundly rich art. Among my favorite films of all time is Synecdoche, New York. It is written and directed by Charlie Kaufman, and it deals with loneliness, meaning, family, beauty, art, genius, and storytelling. It is beautiful and weird and thought-provoking and criminally under-discussed. Plus it stars Phillip Seymour-Hoffman and the title track (at the end of this preview) is absolutely gorgeous. I highly recommend checking it out if you get the chance.

Community as an Antidote to Meaninglessness

I shared the idea for this essay with several people. Two people in particular had funny responses. One person said, “yes, of course. Nihilism really only appeals to single, wealthy people.” Another said, “yeah I remember reading those things in school and thinking it was just . . . silly? Like, there is so much to philosophy and Nihilism just seems so silly and disconnected from reality–especially my reality with a big family and people who rely on me.” It made me wonder how much of my perspective was informed by being a father, and conversely, how much of Nihilism, Absurdism, Existentialism etc. was informed by the fact that many of these philosophers were lonely, educated men. Anyway, this is the one-year anniversary of one of my favorite essays I’ve written about family:

https://charliebecker.substack.com/p/what-becoming-a-father-taught-me

Bulletin Board

Castles in the Sky News

A friend gave me some good advice recently. He was measured, precise, and gentle in giving advice, but it’s easier to remember what he said and make it actionable if I imagine him as a 1970s-era Hollywood producer:

“Content, baby! That’s the name of the game: give the people what they want. Save the explanation for later. Let’s see some action, sweetheart.”

In other words, I was being too meta before. I can write things, and I can write about myself, and I can write about writing, but I could stand to do less writing about myself writing things. Hence the new format you may have noticed for Castles in the Sky.

I’m going back to publishing once a week. Every Friday I’ll jump right in and get right to the meat: essay, book review, profile of another writer, etc. No more long intros or tangents. Any meta news and updates will go at the end.

Shout Outs

Since this is my first weekly newsletter in a while, here’s everything that I wrote in August along with some of my favorite comments from each.

For Richer or Poorer is a love letter to weddings: why they’re special, why to have one, and how to make it a good one.

In Questions Lead to the Good Life, I explore the power of psychological richness, and how asking questions about everything has given me a great life.

The Power of Being Weird I tell the story of two friends I met in China, and how being weird (or a perpetual noob) can be your superpower.

The Bookseller's Register #1, I introduce a new series leaning into my destiny: a chronicle of my journey to join the family business and build the used bookstore of the future.

The Bookseller's Register #2 I talk about my favorite section in the bookstore, Paperback, and why it is a great microcosm for the store itself, showing how people have forgotten how great algo-free browsing can be.

Relatable Flaws | Review of Ask the Dust by John Fante is a review of the classic novel interwoven with personal stories about my own insecurity and confusion trying to be a young man, occasionally in love, trying to find my way in the world.

For the last monthly newsletter issue, check Castles in the Sky 35.

Thanks for reading!

See you next Friday. Do you like the new format? Let me know what you thought in the comments and share it with a friend who might be interested.

Camus is not nihilistic. Absurdism advocates the following: (1) the fundamental characteristic of existence is the conflict between our desire for meaning and the universe's indifference; (2) the proper response to this fact is not to deny it (nihilism) or escape it by making claims to meaning you find/create (philosophical suicide / bad faith) but to revolt and live within the absurd; (3) a life lived this way is one that is honest and authentic, but it will not offer resolution or reconciliation.

I totally hear you about being bored or repulsed by Meursalt, but The Stranger (like all of Camus fiction) does not positively express a philosophical position. Rather, Camus's characters highlight the difficulty of confronting the absurd, and their flaws illustrate how one could accept the absurdity of existence yet fail to revolt. If anything, his characters' philosophies should be read as an a half-antithesis to Camus's. The real value in The Stranger and The Fall, for instance, is that they enumerate the many ways we delude ourselves and the many ways the absurd can eat you, what it looks like to fail to revolt.

Meursalt is an unhappy Sisyphus. Camus advocates for a way of living where, even though we're trapped within a Sisyphean struggle, we can still be happy and grateful and where we can still enjoy existence.

I grew up in a somewhat religious household, but when I was around 16 I lost my faith. I read some philosophy and literature, read through some different religions but fundamentally I didn't really believe in anything anymore. Looking back, I fell into nihilism for years, but it wasn't a conscious choice or philosophy I followed. I just stopped believing in anything and ended up a very very unhappy person. So over the years I suppose I've created my own meaning built up a new structure to "justify" my existence in a world that seems to lack meaning. What I'm trying to say is I love Absurdism and I love your essay thanks for writing.